In countries with national flag carriers, there are leisure airlines that offer flights to more international countries. In the U.S, this model doesn’t work.

While researching our latest article about Wizz Air’s transatlantic narrowbody ambitions, a curious idea came to mind: the United States has no dedicated intercontinental leisure carrier. Countries like Canada have Air Transat, France has French Bee and Air Caraïbes, Germany has Condor and Discover Airlines. Where’s America’s version?

The answer is pretty simple. The U.S. airline market doesn’t need one. Whether that’s good or bad depends on your perspective, but the overall economics of such an operation tell a clear story.

First, we’ll better describe what we’re talking about. Yes, U.S. carriers fly to vacation destinations internationally. But what we’re discussing isn’t quite the same thing.

In some countries, a national flag carrier dominates international flying. British Airways connects nearly all major cities across the world to England. Air France and Lufthansa do the same for their respective countries. These airlines control international access and, by extension, pricing.

The U.S. operates differently. We don’t have a single flag carrier, but a roster of three major “legacy carriers”: Delta, American, and United, who handle most long-haul international flights.

Low-cost carriers like JetBlue and Southwest serve regional leisure markets in the Caribbean and Latin America, but their overall business success doesn’t hinge on going head-to-head with legacy carriers on intercontinental routes.

The difference in other countries is that leisure-only carriers help fill the gap created by flag carriers. They serve as cheaper alternatives to expensive flag carrier “monopolies.” TUI Fly, Wizz Air UK, and others exist because travelers need cheaper options. Some fly to leisure destinations across Europe, the Middle East, and as far as the Americas.

The U.S. market structure with its ample choices makes international-only leisure carriers unnecessary and unpractical.

The main benefit of dedicated leisure carriers is price. When flag carriers dominate the market, prices begin to climb. Flying, let alone traveling with a family, becomes an expensive commodity.

International leisure carriers help change this equation for budget-conscious travelers. These airlines run with lower operating costs, rely on seasonal schedules instead of year-round daily service, and simply better cater their business to these types of customers. They know their audience and build around it.

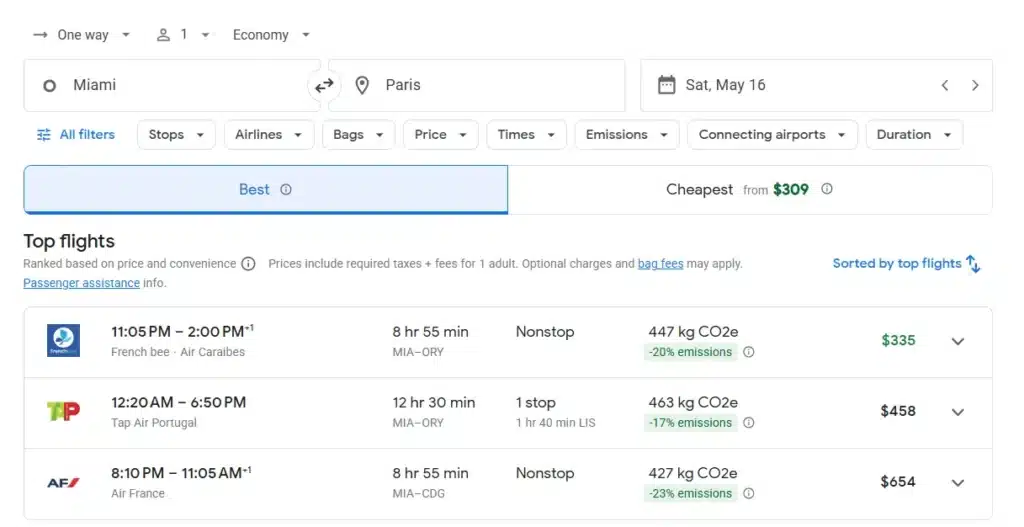

For example, we’ll examine French Bee versus Air France on a Miami-Paris route pairing. French Bee charges around $355 per passenger for a one-way economy seat. Air France, on the other hand, charges $655 for the same seat. For people flying on a budget, that’s not a small difference. It’s the difference between being able to afford the trip or not.

You can learn more about ultra low cost flying overall by checking out our guide here.

The real reasons dedicated international leisure carriers don’t work in the United States come down to network structure and market competition.

U.S. airlines, for the most part, rely on hub-and-spoke systems. They funnel passengers from smaller markets to these large hubs, then out to destinations, especially international ones. This allows for consistent demand across most routes.

European carriers greatly utilize point-to-point service, which leaves room for smaller seasonal leisure operators to cherry-pick profitable routes.

A point-to-point international leisure carrier based in the U.S. would struggle to generate sustainable passenger loads. A comparison would be Frontier Airlines and EasyJet UK.

Both are ultra-low-cost leisure airlines. They also use a fluid point-to-point system. As a wildcard, we’ll also include Sun Country Airlines, another ultra-low-cost leisure carrier in the U.S. that uses a hub-and-spoke model.

| Airline | Passenger Loads (Nov 2025) |

| EasyJet UK (Point-to-Point) | 90% |

| Sun Country Airlines (Hub-and-Spoke) | 85% |

| Frontier Airlines (Point-to-Point) | 78% |

As shown in the table above, EasyJet’s point-to-point model works better in Europe than Frontier’s point-to-point system does in the States. Their passenger loads are much higher than what Frontier generates. Sun Country, which showcases the U.S.’s preferred hub-and-spoke model, ranks second in the country when it comes to load factors. It still ranks behind what EasyJet gets in Europe, but it’s an improvement over Frontier.

A U.S. leisure international airline would struggle with profitability using a point-to-point system, as they’d likely have trouble generating adequate passenger loads.

Nearly all U.S. airlines offer basic economy fares. Whether you’re flying United, Delta, American, or an ultra-low-cost carrier like Spirit, there are minimum seating arrangements priced at the cheapest rates available.

Now there is a spread between what ultra-low-cost and legacy carriers charge fare-wise when it comes to these economy seats, but it’s not the dramatic gap you see in countries with dedicated flag carriers and their leisure competition.

This competitive pricing eliminates the value proposition of dedicated international leisure carriers in the United States. American consumers already have budget options without needing another ultra-low-cost airline niche.

Contrary to Canada with the dominant Air Canada or European countries with single flag carriers, the U.S. airline market has robust competition. Multiple U.S. carriers serve the same international routes, which helps balance the prices passengers pay.

The capitalistic environment of the U.S. airline industry solves the problem that leisure carriers address elsewhere.

If a dedicated international leisure carrier were to launch in the U.S., it would have to operate under pretty strict parameters:

Charter or Ultra-Limited Service: Flying daily flights could be economic suicide. The airline would need to fly when demand justifies it, building up load factors before scheduling flights. This means longer booking windows and overall less flexibility for travelers.

Surgical Route Selection: Missing the mark on destination choice would be fatal. The airline would likely need to base operations from a large metro city like New York for population density, then service only the hottest leisure destinations with minimal legacy carrier competition. It would be akin to what JetBlue is doing with their transatlantic product.

The Right Aircraft: The Airbus A321XLR is the only realistic choice. Widebody planes require too many passengers to reach breakeven load factors and present strict infrastructure requirements, which could limit the places this hypothetical airline could fly to.

Even if the airline has all these factors aligned, the odds are still stacked against its success.

The most notable example of this type of airline based in the United States was ATA Airlines, which flew as a low-cost scheduled carrier with an arm for charter flights. The airline was hit hard by the downturn of the airline industry due to the September 11th attacks, shrunk its fleet and network as a desperate attempt to right the ship, but ultimately was never able to get back on course. ATA offered a slew of vacation destinations throughout the United States, including flights to Florida, Las Vegas, and Hawaii, as well as international flights to nearby countries and transatlantic routes to Europe.

Pan Am is attempting yet another comeback. A new entity has purchased the naming rights and promises to bring a “modern twist” to operations.

Pan Am’s history proved to be as close as the country has come to having a national flag carrier, as it dominated international travel for decades. Could this revival be the answer to whether the country will support a dedicated international leisure airline?

Probably not. The new Pan Am won’t reach the scale to compete with Delta, American, and United. They won’t pivot toward low-cost domestic routes without betraying Pan Am’s legacy. And it’ll be hard for them to undercut legacy carriers on price while trying to maintain the Pan Am brand positioning, if they choose to go down that road.

The realistic play for them would be charter or sporadic long-haul service to uncommon leisure destinations. The summer 2025 Pan Am revival, featuring a Boeing 757 in Pan Am heritage livery operating short-term charter flights, presents a compelling template for this new airline to use. It celebrated nostalgia without pretending to be a full-service carrier.

But even that faces long odds.

The U.S. doesn’t have dedicated long-haul leisure carriers because our market doesn’t need them. Hub-and-spoke operations, competitive basic economy fares, and the number of airlines flying the same international routes naturally create the positive environment that leisure carriers provide elsewhere for countries with flag carriers.

In Europe and other parts of the world, flag carriers create pricing power that hurts consumers at times. Leisure carriers emerge in these areas as a market correction. In the U.S., the airline market has already corrected itself.

Pan Am’s latest revival might take a run at becoming an international leisure-only U.S.-based carrier, but without a strategy to create differentiation in an ultra-competitive market, it’s hard to see how they would gain traction beyond nostalgia flights.

The absence of dedicated international leisure carriers in the U.S. isn’t a market failure. It’s proof that the market is working.