Delta Air Lines has been very clear. No narrowbodies on transatlantic routes. They’ve doubled down on their widebody fleet sticking to their core values.

United and American are battling it out to see who can better fly narrowbody planes across the Atlantic. They’re flying to smaller European cities like Porto and Madeira with single-aisle aircraft. These planes like the Airbus A321XLR and Boeing 737 MAX are fuel efficient and have the range to make this type of flying possible and economical.

But Delta is moving in the opposite direction. They just ordered 30 Boeing 787 Dreamliners and made a pledge only a few months ago to fly only wide-body planes across the Atlantic.

Who is going to come out on top? Is Delta missing out by avoiding these smaller European cities, or is their widebody-only strategy a stroke of genius from an airline that understands its customers?

The answer comes down to economics. How much money these airlines are making per flight. And we suggest that Delta has figured out something their competitors are missing.

Simply stated, Delta is putting all their chips on their business and first class experiences. They’re betting that the revenue they generate from business and first class passengers will make up most and exceed what they’d make from flying directly to smaller European cities.

It’s simple mathematics and economics.

The amount of revenue you generate per flight is directly related to the number of passengers each plane can carry and which cabin they’re sitting in:

American Airlines Airbus A321XLR – Philadelphia to Porto: 20 business class seats, 12 premium economy, 148 economy class

Delta Air Lines Airbus A330 – New York JFK to Paris: 34 Delta One Suites, 28 Premium Economy, 56 Comfort+, 168 Main Cabin

If both these planes are fully packed, Delta should come out on top revenue wise.

In this small city versus big city transatlantic route pairing shown above, Delta is already configured to carry 70% more business class seats than American.

Business class customers pay significantly more than standard economy passengers. Sometimes 3-5 times as much. On top of that, Delta’s A330 carries more total economy seats, so American can’t make up the lost business class revenue through economy passengers alone.

But this advantage only holds if passengers actually buy those seats. Based on 2025 data, Delta led all three legacy carriers with the best load factors on all international flights:

| Airline | International Load Factors (2025) |

| Delta Air Lines | 84.94 |

| American Airlines | 84.39 |

| United Airlines | 81.06 |

While this includes all widebodies, narrowbodies, and poorly performing global international routes, all signs point to Delta slightly outpacing the other two airlines on flights to Europe when looking exclusively at United & American using narrowbodies and Delta just using widebodies.

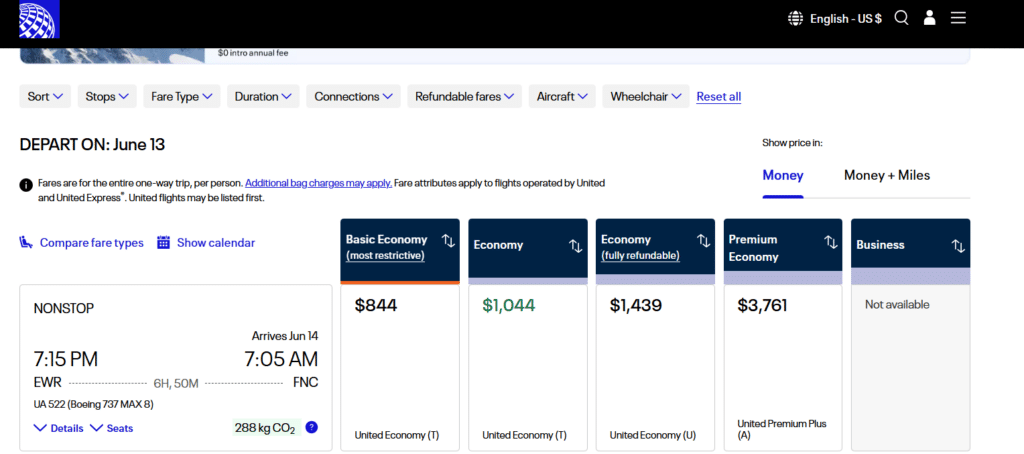

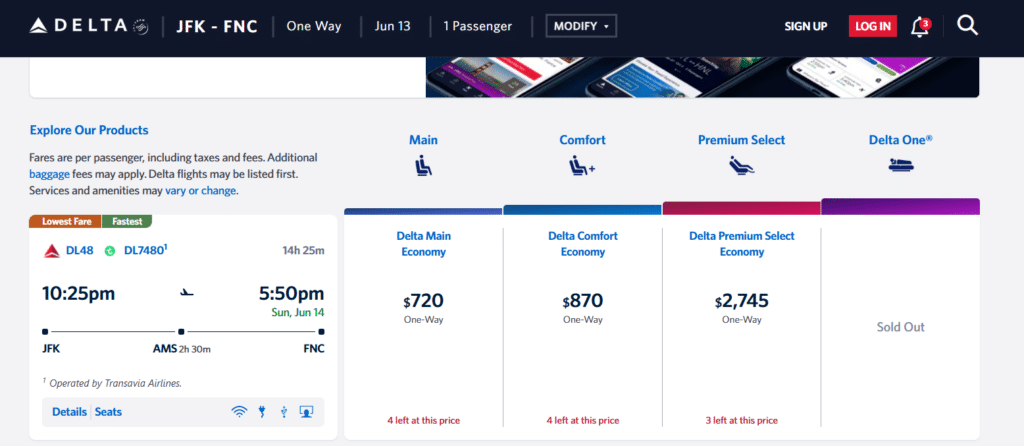

Consider this real-world comparison: United’s latest narrowbody service to Madeira with their Boeing 737 MAX 8 versus Delta’s service through Amsterdam.

United offers a nonstop flight while Delta requires a stop in Amsterdam before continuing on a connecting flight with partner airline Transavia. You’ll get there quicker with United, but the ticket prices across economy and premium economy are often more expensive than what Delta charges. Which makes sense given the timing convenience factor.

But here’s where Delta’s strategy pays off: The Delta flight into Amsterdam uses an Airbus A330-900neo which fits 281 passengers, while United’s MAX 8 fits only 166. More importantly, Delta offers a full business class cabin on the Amsterdam route, while United doesn’t offer business class on the leisure-focused Madeira flight.

Delta will simply make more revenue per flight to a major European city than United will flying to secondary European destinations with narrowbodies. Customers end up in the same place, though it may take longer with Delta. But they’ll likely pay less and be more comfortable. Delta’s bottom line gets padded more firmly than United’s in this scenario.

Here’s something people have forgotten: Delta already actively flies and one time more prominently flew narrowbody planes across the Atlantic. They use their Boeing 757s almost exclusively to fly to Iceland. These 757s are actually larger and fit more passengers than the Airbus A321XLR.

Here’s why Delta uses the 757 only for Iceland routes:

It’s a relatively short flight. Iceland sits between North America and Europe. The flight is about 2,400 miles from the East Coast.

Nearly everyone on the plane is traveling for leisure. Iceland isn’t really a business center. Delta’s 757s use mostly high-density layouts with some seats labeled as premium.

Iceland is a hot commodity. There’s plenty of competition for flights to Iceland. Is it worth Delta committing their widebodies? No. Is it too hot to ignore? Yes.

This example reveals why Delta’s widebody transatlantic strategy works. The Boeing 757 is more than capable of flying to many European cities. United actually still uses them on some routes. But Delta simply doesn’t deploy them more broadly because the economics don’t work.

As already stated, Delta’s 757 holds 235 passengers, which is more than what American carries on their Airbus A321XLR (180 passengers). If narrowbodies to Europe were truly profitable across the board, Delta would be using these planes on flights to just about every high-demand Secondary European city. Instead, Delta is retiring these planes because they’re old, have high operating costs, and other planes in Delta’s fleet are better suited to handle the job the 757 currently has which is domestic hub turns.

Delta’s 757 transatlantic flights were common in the 2010s, but most routes were eventually canceled:

| Destination | Year Ended |

| Malaga | 2019 |

| Pisa | 2016 |

| Ponta Delgada, Azores | 2019-20 |

| Valencia | 2012 |

| Stockholm | 2017-18 |

United operated one of the longest 757 routes for a long time, Newark to Stockholm but even they cut this route due to poor demand.

It’s true that today’s narrowbodies are more cost-effective to operate than the 757, but the demand factor doesn’t change. Airlines have to nail their market research or run routes only part of the year. Delta doesn’t want to deal with that headache especially when they can guarantee profit on runs across the pond to major European cities using widebodies.

The Airbus A321XLR is an impressive plane that will likely have a great service history. Its range is unparalleled. It can fly up to 4,700 miles, covering just about all transatlantic routes.

But here’s something it can’t do as well as a widebody: provide a comfortable flight experience for 7-8 hours.

In a recent review, One Mile at a Time flew on American Airlines’ transcon A321XLR service. Passengers complained about cramped business class, limited lavatories, and other issues. All simply realities of flying narrowbodies for long distances.

A narrowbody plane is typically 12 feet wide on the inside. A widebody is about 18 feet wide. To put this in perspective, the diameter of a Boeing 737 fuselage is about the size of a Boeing 777 engine. This difference in cabin width makes a huge impact on comfort, especially in business class where passengers pay premium prices for space and privacy.

It’s no secret that Delta tries to maintain a high level of premium service for its customers. Their Delta One business class includes full suites with closing doors. Something you cannot offer on a narrowbody without sacrificing a significant number of seats.

Flying narrowbodies could potentially mean offering an inferior product, which contradicts everything Delta stands for.

In December 2025, Delta ordered 30 Boeing 787 Dreamliners with an option for 30 more. This is one of the boldest statements the airline has made about the direction it wants to go. This came right after United and American announced their continued exploration of narrowbody transatlantic flights.

What this tells us: Delta is looking to replace their older Boeing 767s with the more fuel-efficient 787s. It also signals that Delta will likely move some of their Airbus A330s (currently used on Pacific flights) to serve the Atlantic routes, supplementing capacity between Europe and North America. They will also use the 787 across the pond and down towards South America.

They’re also soon to receive Boeing 737 MAX 10s, which will replace the Boeing 757 on domestic cross-country routes. But there are no plans for long and thin transatlantic routes for the MAX 10s.

All this means Delta is doubling down on the widebody fleet. The most interesting aspect is that they announced this order while watching American’s and United’s moves on the transatlantic front.

The 787 is important to Delta because it future-proofs the airline, aligning them more closely with what their SkyTeam partner airlines are doing. Air France and KLM are both updating their fleets with top-of-the-line ultra-long-haul planes. They’re not flying narrowbodies across the Atlantic, and they share Delta’s strategy of promoting premium experiences.

If you’re choosing which airline to fly across the Atlantic, Delta’s widebody strategy has both benefits and tradeoffs.

Delta’s advantages:

United/American narrowbody advantages:

However, remember that Delta still flies to major European cities—you’re only a short connection away from your final destination. With the added stop, you can also experience a different city if you choose, all on a single ticket.

Who benefits most from Delta’s approach?

Who benefits most from United/American narrowbodies?

Delta isn’t ignoring narrowbody transatlantic flights because they’re stuck in their old ways. It’s a calculated business decision about what will make them the most money in the long run.

By sticking to widebody planes, Delta can:

Delta also has history to fall back on. They flew long and thin routes with their Boeing 757s throughout the 2010s. Today, Delta continues to use their 757s on only one transatlantic route. A relatively short, leisure-focused trip to Iceland that doesn’t generate significant premium revenue.

For travelers, it means you have a choice. If slightly lower costs or direct service to secondary destinations is what you seek, United or American might be your answer. If you want to fly in comfort or luxury, a Delta flight to a major European city with a connection might work better for you.

As for the overall winner of this strategy battle, Delta’s widebody approach will likely prove more sustainable for the airline in the long term. The premium revenue model, combined with hub efficiency and brand consistency, creates a defensible competitive advantage. However, different travelers have different preferences and that’s exactly why both strategies can coexist in the market.